100 years ago, a fight against a new German advance in Northern France was developing into a defining moment for the US Marines. The first full American-led offensive of the Great War had resulted in the capture of Cantigny in the Somme as May ended. But June opened with the Allies struggling to contain a German thrust towards the Marne, northeast of Paris. After three days of mounting casualties in and around Belleau Wood, American and French commanders decided that the time had come for a new approach. The Marines in action there had to date shown bravery and resolve but to little effect. Planning in the run-up to the initial assault had been flawed, as Patrick Gregory explains.

The American commander at Belleau Wood, Major General James Harbord, pictured after World War I (Photo: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection)

By midday on 8 June, two days into the fighting, it was clear that little headway was being made in Belleau Wood. Units of the 4th Marine Brigade were fighting a losing battle against an unseen enemy lurking deep within.

Among the brigade’s units, the 3rd Battalion of the 5th Marine regiment had been all but destroyed. Sibley’s battalion from 6th Marines had fared little better and had been stuck at the southern edge of the wood. In truth, the operation against the woodland had been flawed from the start: poorly planned and badly executed.

Artillery

A new tack was called for. Future assaults were now deemed impossible without “further preparation”; and a lot of preparation was needed. The French XXI Corps, to which the overall force of US 2nd and 3rd Divisions in the area were attached, issued a new directive. Further assaults would be conducted “methodically, by means of successive minor operations, making the utmost use of artillery and reducing the employment of infantry to the minimum.”

The Americans had been in the area for over a week now, following the devastating speed with which Ludendorff’s Third Offensive had cut down towards the Marne. The two divisions had been rushed into there from points east and west to help block the enemy’s path to Paris. The 3rd Division concentrated its forces initially in and around Château-Thierry, the vital bridgehead on the river.

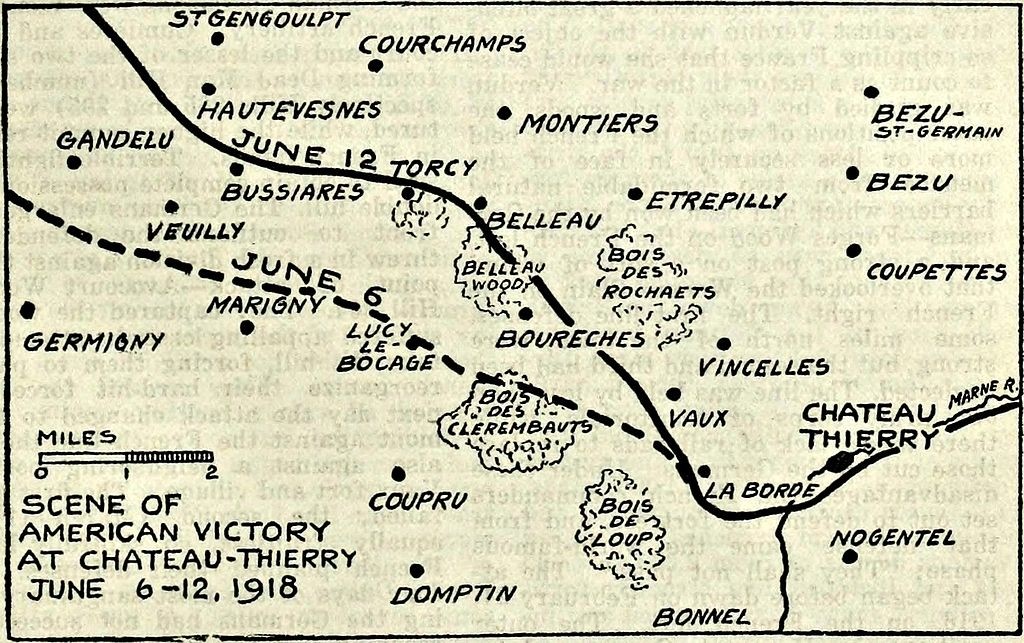

But the main action had since focused north-west of the town. By 4 June the two brigades of the 2nd division found themselves facing across an enemy-held line which took in the villages of Vaux, Bouresches, Torcy and Bussiares. Belleau Wood lay at its heart.

Map showing the battle lines at Belleau Wood and Château-Thierry (Image: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain)

The plan to start taking back this territory began in earnest in the early hours of 6 June. To one side of the wood an area of raised ground, Hill 142, was captured; on the other Bouresches. The decision to press on into Belleau Wood was taken that afternoon.

Unfortunately for the unit mounting the attack from the west – 3rd Battalion of the 5th Marines – insufficient reconnaissance had been carried out beforehand. Little was known as to what to expect when they got there and only scant artillery fire laid down on the wood in advance. It was a mistake. German machine gunners lay in wait inside. And they were there in numbers, in defensive holes, behind rocky outcrops and shielded by dense undergrowth. To make matters worse, the Marines had advanced towards the hidden foe in rank formation over the exposed ground outside. They were slaughtered. Sibley’s battalion of the 6th Marines suffered a similar fate attacking from the south edge. By nightfall, 222 were dead and over 850 wounded.

But still they persisted. Sibley’s men went again the next day and once more on 8 June. With little to show for it, however, the commander of 4th Brigade James Harbord, ordered an intense artillery bombardment before another assault was attempted.

View of Belleau Wood and Bouresches (Photo: Library of Congress/Flickr/No Known Copyright restrictions)

At dawn on 9 June, all 160 field artillery and heavy guns in the sector began to pound the German positions. Twelve machine gun positions were set up to the eastern flank in Bouresches to try to box the Germans in. The Allies could, hoped Harbord, ‘obliterate any enemy organisations’. The guns continued all day and all night.

At 03.30 on 10 Jun the guns intensified their fire and then, after a further hour, became a rolling barrage. Following behind, the 1st battalion of 6th Marines forced their way into the woods from the south. The unit commander Major John Hughes could report that the barrage was ‘working beautifully’ and that they had taken their objectives ‘without opposition’. A mood of optimism began to filter through the ranks and among Marine commanders. But the battle was not over. Not by a long chalk. Early thoughts that the forest and its inhabitants had been ‘blown to mincemeat’ would prove premature. A further fortnight’s fighting lay ahead – and it would be bloody.