As commemorations get underway to mark the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Jutland, a new exhibition examining the battle has just opened at the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich in London. Patrick Gregory took a tour.

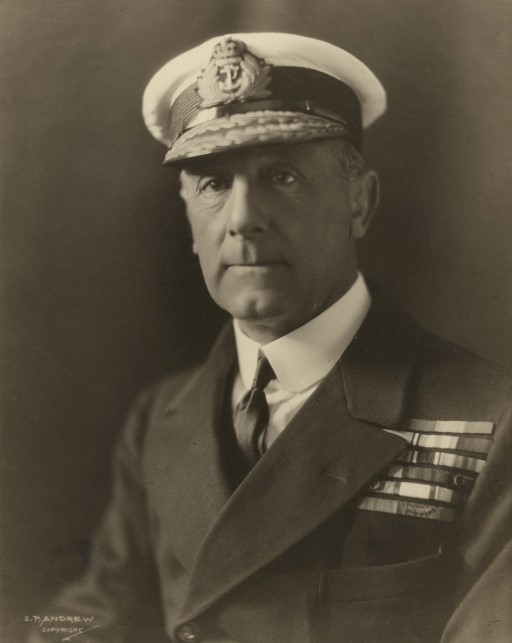

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander-in-Chief of Britain’s Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland in 1916 (Image © National Maritime Museum, London)

‘Jutland 1916: WWI’s Greatest Sea Battle’ is the first exhibition to focus on the encounter at the museum in a full 30 years, one which is to be accompanied by a number of talks over the next few weeks looking both at the battle and the overall role played by the Royal Navy during the First World War.

The talks – and the exhibition itself – seek to position the battle in as broad a context as possible and it begins with an explanation of the pre-war naval arms race. That 20-year period, straddling the turn of the century, was a time of gradually heightening tensions: Britain and Germany engaged in an expensive construction programme, upping the ante in the years leading up to the outbreak of hostilities.

There is space, too, for a human dimension to the exhibition as it seeks to tell the stories of some of those who fought in the North Sea, personal testimonies from widows or former comrades.

Some died in the waters, others survived, including those like William Vicarage who suffered terrible injuries or the boy bugler William Robert Walker, severely wounded on board HMS Calliope and who was later visited as he recovered by King George V and presented with a silver bugle – part of the display at Greenwich – by the Commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe.

The silver-plated bugle presented to William Walker. It’s inscribed “Presented by the Commander in Chief to W.R. Walker, ‘HMS Calliope’, 31st May 1916” (Image © National Maritime Museum, London)

But it is of course the battle itself which occupies the central role, laid out in detail in a series of wall charts, maps and displays at the exhibition; and there is a 10-minute film narrated by the fleet admiral’s grandson Nick Jellicoe, explaining how the two countries’ navies and their detachments of battlecruiser squadrons first skirmished and then fiercely clashed over the two days of battle.

The confusion and ferocity of the conflict is amply demonstrated, the life-or-death decision-making taken by Jellicoe and his opposite numbers, working out which way to turn and the calculations of the dangers lurking in the seas ahead.

There are the early losses on the British side of HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary, losses followed two hours later by those of HMS Defence and HMS Invincible. There are the sudden emergency turns executed by the German High Seas Fleet as it tries to evade the full might of the numerically superior Grand Fleet; and also the Grand Fleet’s manoeuvrings to avoid German torpedo attacks; and finally the last desperate skirmishing in the chaos of night-fighting, as foes attempt to identify one another in the disorientation of a dark night at sea.

8,500 lost

As history recounts, of course, ‘Der Tag’ famously achieved little by way of concrete gain for either side. One of the most heavily anticipated engagements of the war was also one of its biggest disappointments. Over 8,500 lives lost with neither participant able to chart a particular course ahead. Except perhaps this: that the early and rather over-optimistic claims made in the immediate aftermath of battle by German naval commanders, claims as to the damage inflicted on Jellicoe’s armada, soon gave way to the realisation that little had changed.

The British naval blockade was still slowly starving Germany’s wartime economy. The result? A decision taken little more than six months after Jutland by the German High Command: the resumption of a campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare in the north Atlantic and the coastal waters around the British Isles.

In all, the Maritime Museum seeks to use this Jutland exhibition to tell a wider story of naval conflict in the First World War and does so both with the help of British – and some original German – source material, and with a keen eye on how it affected real people.

Using a wide variety of objects and displays – paintings, photographs, plans, medals, maps and models, many on show for the first time – it captures some of the public sentiment alive at the time. A mighty naval engagement and its aftermath, a battle so long in the making but one ultimately which neither country could walk away from with any sense of achievement.