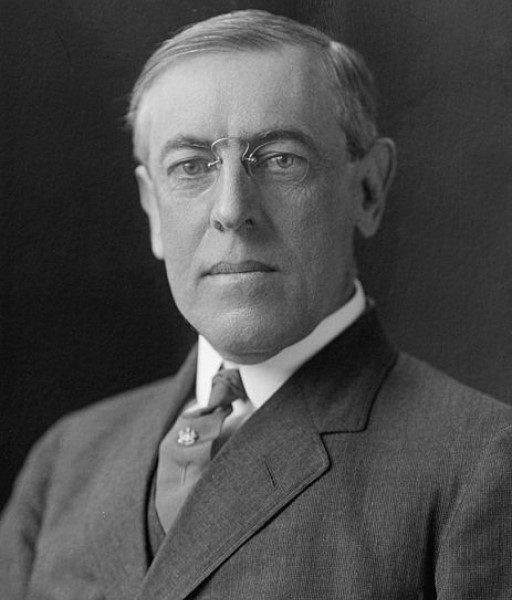

President Woodrow Wilson narrowly won a second term in November 1916 on a platform of ‘He Kept Us out of War’, reflects Patrick Gregory.

As American voters queued on 7 November 1916 to cast their ballots in their country’s elections, few of the country’s leaders – and that included the candidates – could have guessed that only a few months later the country would find itself at war. The campaign of the summer and autumn had been a keenly fought one; and the result when it came some days later was to prove cliff-hangingly close. Thoughts of war were far from the mind.

The United States of 1916 was a strikingly different country to today’s America. Still a young union, and with less than a third of today’s population, it was only 50 years on from a Civil War which had so nearly torn the union apart. In fact, a dozen new states had joined in that 50-year period so it was little surprise that this rapidly expanding country was looking more to its own future development and less to the outside world.

Caution

Under Woodrow Wilson, the United States had very deliberately avoided becoming embroiled in the war in Europe; and Wilson was equally judicious in his use of troops south of the border, with a cautious attitude to his intervention in the Mexican Revolution, then raging for six years. The so-called ‘Punitive Expedition’ he had sent in March 1916 led by John Pershing was a deliberately limited affair, attempting – unsuccessfully – to capture the revolutionary leader Pancho Villa, then harrying border areas of the US. The operation was halted after less than a year.

Making a virtue of this caution, Wilson campaigned in the run up to the 1916 elections under the banner ‘He Kept Us out of War, to try to appeal to those voters who wanted to maintain this status quo. His Republican opponent Charles E. Hughes in reply criticised him for not taking the ‘necessary preparations’ to face a conflict, which served to strengthen Wilson’s image as a dove.

Hughes’ Republicans were beginning to get their party back on track after the travails of 1912. Then, their vote had been split by former Republican president Theodore Roosevelt fighting as a third-party candidate for the Progressive Party. Roosevelt had taken on the White House incumbent – and his own former deputy in office – William Taft, netting over 27% of the popular vote to Taft’s 23%. In 1916, however, and although he had been re-nominated by his ‘Bull Moose’ party, Roosevelt had chosen the path of unity to try to stop Wilson, the Democrat whom he had unwittingly helped into the presidency 4 years before.

Crucial

Roosevelt threw his weight behind the Republicans’ choice as candidate, Charles Hughes, a lawyer, and one who now took his fight to the country with vigour. In embarking as he did on his quest, however, Hughes made one early and ultimately crucial error: campaigning in California without calling on or consulting the state’s Governor, Hiram Johnson. Johnson had been Theodore Roosevelt’s vice-presidential candidate for the Progressives four years before, and whether Hughes’ failure to call on Johnson had been calculated as a payback or not, the California Governor appeared to have taken it as a personal slight. His tenure as Governor was coming to an end and in this latter part of 1916 Johnson was seeking election as a senator for the state. That campaign, as well organised as it was, now concentrated solely on his own future and not that of Hughes as Republican presidential candidate.

Precisely what kind of Republican vote might have been mobilised in California in those last weeks of campaigning in 1916 must remain a matter of conjecture, but it is probably enough to say that the state’s hair-breadth loss was to spell the end of Hughes’ ambitions.

The outcome of the vote actually remained in the balance for some days after 7 November as predictions and results swung the contest first one way, then the other. Some newspapers went out on a limb calling it prematurely – and as it turned out inaccurately – for Hughes. Indeed, a story which emerged from the time cites a reporter calling Hughes for a comment on the latest twist and turn of the moment. He found Hughes was asleep, resting. An aide is reputed to have told the reporter that ‘the President’ could not be disturbed. ‘Well’, said the reporter, ‘when he wakes up tell him he’s no longer President’.

Irony

Eventually the national picture saw the two candidates separated by just 600,000 votes out of a combined total of 17.5 million. In California that margin was just 3,800 greater for Woodrow Wilson. On 10 November, after some days counting, the 13 Electoral College votes of California finally pushed Wilson over the line.

The irony for Wilson was that lying in wait for him only months later was a decision by the Imperial German Government to resume unrestricted U-boat warfare against America, a move which was to propel the United States to war. Within weeks of his inauguration, in March 1917, the president who had so optimistically fought his re-election under the slogan ‘He Kept Us out of War’ would be preparing his people for just that eventuality.