Reviewer Andy Moreton is moved by this story of Clifford Kimber, a student from Stanford University, California, who signed up soon after the United States declared war in the spring of 1917.

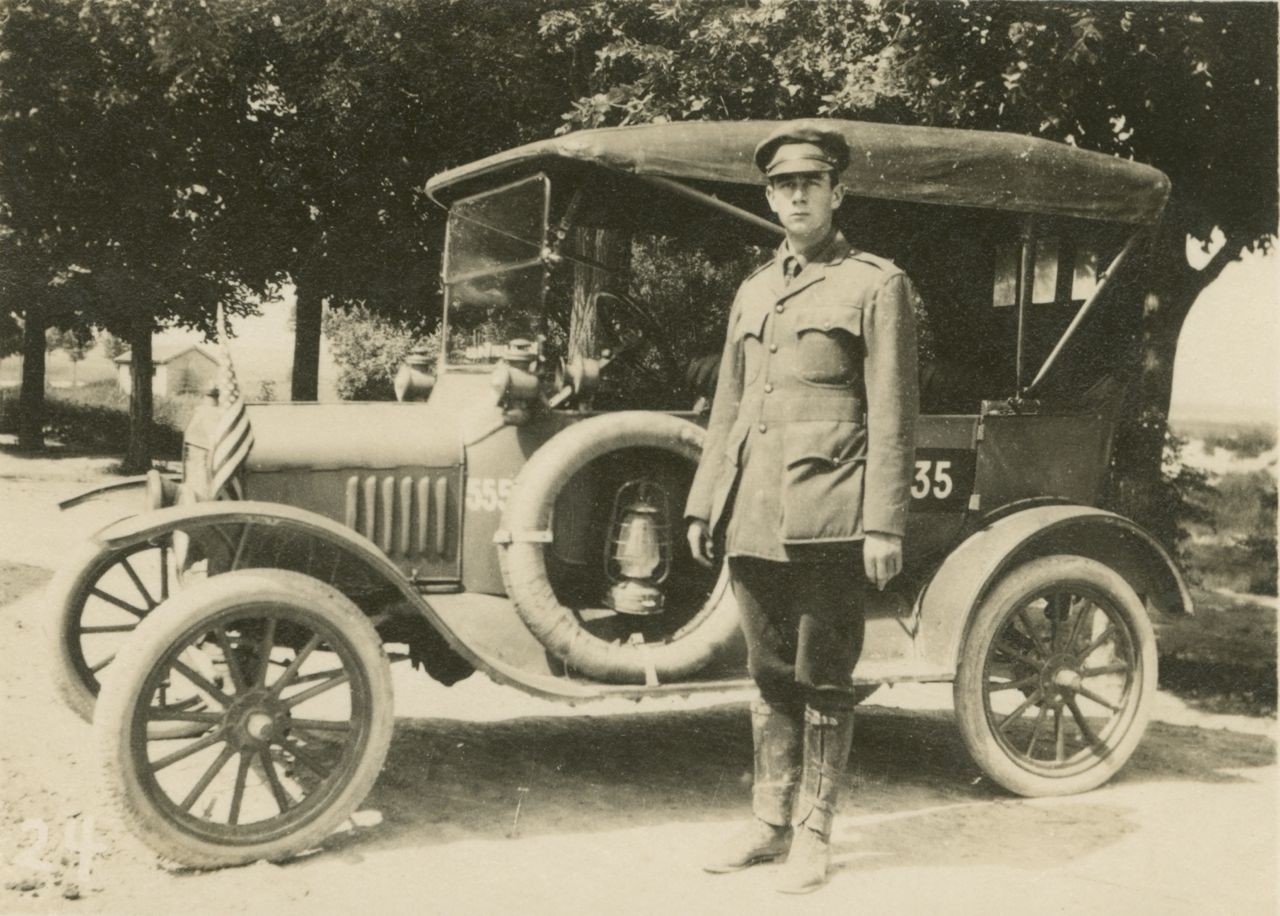

Clifford left his home in Palo Alto to become a volunteer ambulance driver in the 2nd Stanford Unit and in his safe keeping was the first official American flag to go to the Western Front.

After a journey across the States during which he collects a personal good luck note from his hero, Theodore Roosevelt, he sets sail from New York on the steamship St Louis, to arrive at the Front via London and Paris. On board, he has a somewhat gauche encounter with the silent movie star, Lillian Gish.

The many letters home to his mother and two brothers are searingly honest and surprisingly detailed with sketches, maps and photographs. It’s clear that Clifford sees them as an archive or memoir to be worked on after his return from the war and is anxious that they’re kept safe.

We know from the outset that, sadly, he did not survive, so the letters in which he foresees his future with his brothers as successful chicken farmers are unbearably poignant: ‘

Personally, I sort of believe I have a guardian angel and that it will be the other fellow that will get killed. You are going to see me home when this awful war is over and we shall have many happy years together and shall have a most wonderful home of four, and a great time on the farm.’

Arthur Clifford Kimber with staff car of Section 14 & the French 55th Infantry Division, June 1917 (Photo: Kimber Literary Estate)

The early letters betray Clifford’s annoyance at perceived injustices and slights. He rails against pacifists, shirkers, swearers and roisterers. He was, clearly, not an easy companion, with his self-confessed ‘disagreeable conceit’. One of the letters explains how his close friend (and fellow Stanford student), Alan Nichols, had taken him aside gently to point out his flaws, and he’s a much more amenable team-player from then on.

Clifford’s dream is to move from his ambulance duties to train as a pilot. His enthusiasm had been fired years before: when he was 12, he had been among the crowd in France when Wilbur Wright took an experimental flight over a racecourse south of Le Mans.

After an agonisingly long wait, he’s accepted at flying school. The letters about his training and his subsequent experiences as a fighter pilot offer a truly remarkable and colourful insight into the perilous existence of those young pioneers in the skies above France: ‘I watched my tail like a cat and saw the enemy come on … No sooner would I avoid one than another was firing at me. Rat-tat-tat-tat. What a sound … I’ll bet a hundred bullets came within six inches of my body … I didn’t even have a chance to fire a shot.’

Throughout the narrative, the Kimber watchword is ‘duty’ and the frequent set-backs are invariably shrugged off as ‘C’est la guerre.’ The death in combat of his friend and confidant, Alan Nichols, does hit him hard, but his dedication is unwavering: ‘This sad news does not make me hesitate or feel timid about going to the lines. On the contrary, it makes me yearn to be there. Don’t worry about me. “To every man upon this earth death cometh soon or late.” What if I am killed? Could any form of death be more glorious?’

Clifford Kimber was killed in action on 26 September 1918 – a few weeks before the end of the war. The fact that his story is available now for all to see is a tribute to the loving and careful preservation of his archive by his family, particularly his niece, Elizabeth Nurser. She and her son-in-law, Patrick Gregory, a former senior BBC journalist, have skilfully interwoven the letters with context and background. It’s a thoroughly enjoyable read: a story both illuminating and intensely moving.