On 6 April 1917 America finally entered the First World War.

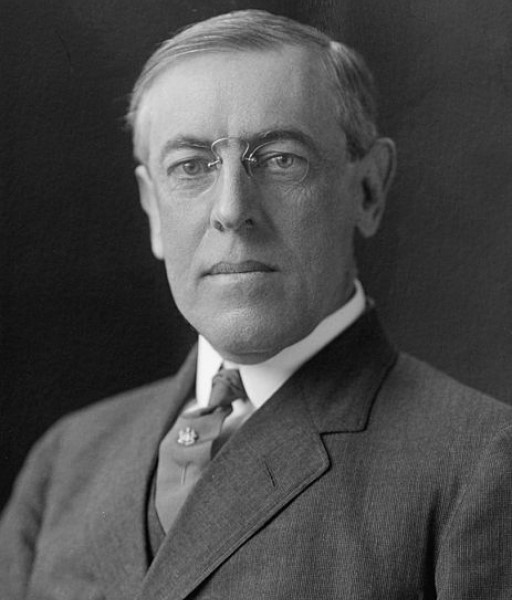

CN’s Patrick Gregory looks at the background to the decision to go to war against Germany, and the forces which propelled President Woodrow Wilson and his country to the battlefields of Europe.

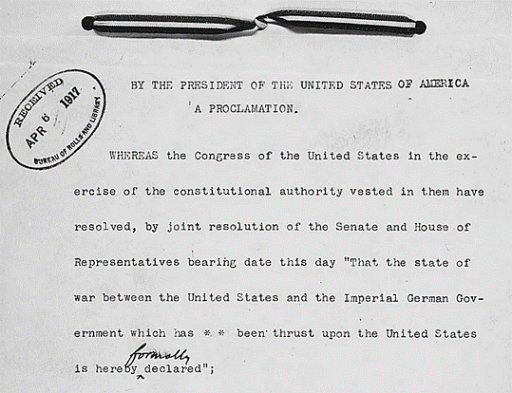

‘Therefore be it resolved by the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that the state of war between the United States and the Imperial German Government which has thus been thrust upon the United States is hereby formally declared’.

The formal declaration of war by America on Germany, a joint resolution by both houses of Congress and the President, was signed on 6 April 1917 by the Speaker of the lower house, Champ Clark, and Vice President Thomas Marshall, presiding over the Senate. The following day Woodrow Wilson added his own signature but the die had already been cast.

U-boat campaign

The slide towards war had begun just over two months before, the result of a decision by the Imperial German Government to resume its ‘sink on sight’ U-boat campaign– the targeting of any and all shipping, including American vessels – in the coastal waters around the British Isles.

It was a situation Wilson had done his utmost to avoid over the preceding two and a half years, enduring the brickbats and howls of anguish which came his way from opponents demanding active intervention in Europe. But a man who had been troubled by what he saw of war – Civil War – in his own native southern states as a child, resolved to keep his and his country’s nose out of the conflict: a conflict whose causes and objects he viewed as at best obscure. American foreign policy would not, he felt, be advanced by participation.

The neutrality Wilson pledged his country to had endured in the intervening period, albeit against the background of an ever-closer alignment of the wartime economies of the United States, Britain and France and an increasingly anti-German sentiment pervading American public opinion.

Caution

But still, the President’s brand of watchful caution held sway. Making a virtue of this, he even campaigned for re-election in 1916 under the banner: ‘He Kept Us out of War’. He won, albeit with the slimmest of margins, with the Electoral College votes of California finally pushing him over the line. By January 1917 Wilson was even daring to look to the future, addressing the Senate in a speech where he asked members of the upper house to help him in his quest to forge the ‘foundations of peace among the nations’ once conflict was at an end.

So when the turn in events came, changing the President’s outlook, it came suddenly and abruptly. Barely over a week after his speech to the Senate, the German ambassador in Washington, Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, called on US Secretary of State Robert Lansing. He had with him a letter declaring that Germany was to resume its policy of unrestricted U-boat warfare. The clock was now ticking. First diplomatic ties were severed, then a halfway-house of what Wilson termed ‘armed neutrality’ was tried, but events had their own momentum.

Zimmerman Telegram

Public opinion was inflamed by the emergence of a telegram, seemingly from the German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman, offering military assistance to Mexico if the United States entered the war on the Allies’ side. The proposal, directed through the German embassy in Mexico, was to-the-point: ‘Make war together, make peace together’, said Zimmerman. If they did, Mexico could expect generous financial support to reconquer lost territory in the United States: in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. ‘The ruthless employment of our submarines’, said Zimmerman, would compel ‘England’ to make peace in a few months. Was it real? Did he actually send it?

Some detected a cynical motive behind it from those on the Allied side who had an ulterior motive, wanting to see America in the war. But the answer was ‘yes’. On 29 March, ending any lingering doubts which remained as to the telegram’s authenticity, Zimmerman himself dispelled them in public. The minister addressed the matter in a speech admitting that its contents were true, even pressing home and justifying his argument with reference to the ‘hostile attitude’ of the American government.

War

So it was on 2 April 1917 April that President Wilson found himself before a joint session of the United States Congress. Congress should declare German actions to be nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States, he said. Armed neutrality had been ineffectual. It had proved impracticable in defending shipping against attack from ‘outlaw’ German submarines.

‘We have no quarrel with the German people. We have no feeling towards them but one of sympathy and friendship’, Wilson insisted. But the ‘world must be made safe for democracy……We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion’. Two days later the Senate voted in favour of Wilson’s resolution, and two after that came the final endorsement of the House of Representatives. America was at war.